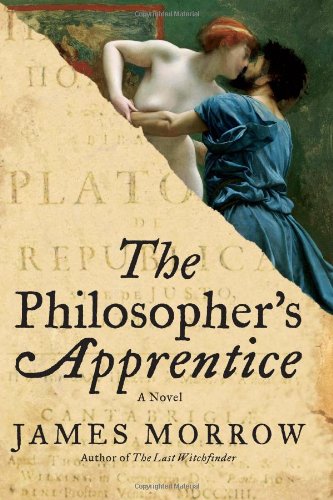

A brilliant philosophy student with a talent for self-destruction, Mason Ambrose gratefully accepts an offer no starving ethicist could refuse. He must travel to a private tropical island and tutor Londa Sabacthani, a beautiful, brilliant adolescent who has lost both her memory and her moral sense in a freak accident. Londa’s soul is an empty vessel—and Mason’s job will be to fill it.

A brilliant philosophy student with a talent for self-destruction, Mason Ambrose gratefully accepts an offer no starving ethicist could refuse. He must travel to a private tropical island and tutor Londa Sabacthani, a beautiful, brilliant adolescent who has lost both her memory and her moral sense in a freak accident. Londa’s soul is an empty vessel—and Mason’s job will be to fill it.

But all is not as it seems on Isla de Sangre. Londa’s reclusive mother is secretly sheltering a second child whose conscience is a blank slate. Even as the mystery deepens, Mason confronts a frightening question. What will happen when Londa, her head crammed with lofty ideals and her bank account filled to bursting, ventures out to remake our fallen world in her own image?

Buy the Tree-Book or E-Book at Amazon

Buy the Tree-Book or E-Book at Barnes & Noble

Buy it at IndieBound

* * *

WHAT THE CRITICS SAID

“An ingenious riff on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene, with ongoing commentary on antiabortion activists and satanic academic pride tossed in … Hold on tight and enjoy the giddy thrills…”

NPR’s Fresh Air

“Morrow addresses controversial topics without being heavy-handed and infuses the narrative with a wit that pragmatists and idealists alike will appreciate.”

“If Plato, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche decided to tie one on, paint the town red, and then write a novel, they might be able to come up with something like this. Morrow’s take of a sarcastic moralist and his unique protégé shocks and perplexes, while taking the reader on a marvelous adventure.”

“Morrow’s world is one where ideas matter so much they come lurching to life as intellectual Frankenstein creatures. In The Philosopher’s Apprentice, they are wickedly hilarious—and then they can break our hearts and scare us silly.”

“Aristotle is referred to so often in this brilliant comedy of manners as to seem to be alive. Also present are Plato, Lawrence Kohlberg, Kant, Sartre, Heidegger, Gadamer, Rawls, Piaget, Captain Kangaroo, and Mister Rogers. How can a novel so loaded with ideas be so funny and consistently engrossing? … Morrow is an inventive writer possessing a fine comic sensibility; the story is infused with wit and brio … Enthusiastically recommended.”

(starred review)

“James Morrow’s fiction isn’t for the faint—the faint of heart, the faint of mind, or the faint of faith. Morrow roasts sacred cows, pokes holes in conventional wisdom, and raises thoughtful, if uncomfortable, questions about the nature of God and the nature of humanity.”

“Morrow is even more inventive than Vonnegut and has Vonnegut’s willingness to milk every sacred cow in the pasture … but The Philosopher’s Apprentice is not just a collection of comic gestures. It can be unexpectedly moving, with scenes of great literary ambiguity. Morrow takes on the issue of abortion is a complex, haunting sequence that could be a novel in its own right.”

“[A] tumultuous take on humanity, philosophy, and ethics that is as hilarious as it is outlandish … [A] wildly ambitious morality play, a shrewd amalgamation of the sacred and the profane. Tips its hat with style to Mary Shelley and George Bernard Shaw.”

“With a talking iguana, a tree with a heart, and an army of clones created from aborted fetuses, Morrow’s latest is a treat for readers willing to take an imaginative leap … Morrow guides readers through preposterous plot points without sacrificing plausibility. Strong characters, shots of humor and an unpredictable narrative make this a winner.”

* * *

|

THE STORY IN BRIEF

|

|

|

Mason Ambrose, a failed philosopher with plenty of smarts but not much common sense, receives what seems like a plum assignment. He must travel to a private tropical island and give ethics lessons to Londa Sabacthani, a beautiful young amnesia victim whose conscience has vanished along with her memories. But all is not as it seems on Isla de Sangre. |

| Londa’s conscience is in fact a tabula rasa, a blank slate, and so she starts taking Mason’s “morality curriculum” — with its emphasis on the radical ethics of the Sermon on the Mount — rather more seriously than anyone intended. Gradually Mason comes to realize that he is not simply influencing Londa’s worldview. He is forging her very being, just as Pygmalion sculpted and then prayed into life his famous statue of Galatea. |  |

|

When Londa reaches adulthood, Mason reluctantly sends her forth into the real world. He fears he has created a “moral monster,” freakish in her outsized superego, but he had no right to prevent her from trying to lead a normal life. At first, it seems that Londa’s idealism will help make the world a better place. She founds Themisopolis, the City of Justice, a utopian community dedicated to the welfare of the oppressed. |

| After Londa’s enemies reduce Themisopolis to ashes, her fight against injustice become more radical than ever. Aided by her loyal followers, she hijacks a new incarnation of R.M.S. Titanic, determined to make its passengers mend their plutocratic ways. When Londa’s scheme turns violent, Mason faces a terrible dilemma: should he destroy the love of his life — this creature he has shaped and ensouled — or should he wait for her to regain her moral compass? |  |

THE PHILOSOPHER’S APPRENTICE

Q: Your new novel, The Philosopher’s Apprentice, has an intriguing title. Who is the philosopher and who is the apprentice?

A: The philosopher is Mason Ambrose, a graduate student at a thinly disguised Boston University who believes he has teased an ethical system out of Darwin’s theory of evolution. During his dissertation defense, Mason crashes and burns, but he still makes a favorable impression on one member of the audience: the emissary of a reclusive biologist named Edwina Sabacthani. The next thing Mason knows, he’s been hired to fly to a remote tropical island and teach his “morality curriculum” to Edwina’s beautiful adolescent daughter Londa — the apprentice of the title — who is evidently an amnesiac with a severely defective conscience.

Q: Does Mason succeed in giving Londa a moral compass?

A: He succeeds all too well. It turns out that Londa’s psyche is really a tabula rasa, a blank slate, and so she ends up taking Mason’s morality curriculum — lessons drawn from Plato, Epicurus, Stoicism, Kant, and the Gospels — rather more seriously than anyone intended. The poor young woman never figures out that she isn’t supposed to really believe the Sermon on the Mount. And so, when she ventures forth from her tropical utopia, she can’t help trying to remake our fallen world in her own morally charged image. Naturally this is a recipe for disaster.

Q: Why is Londa’s mind a blank slate?

A: Shortly after realizing she had a terminal illness, Edwina enacted a scheme that had her making three genetic copies of herself and accelerating their growth to three different stages. Her aim is to experience motherhood in toto before she dies. The plan actually works. Thanks to Londa, Edwina comes to know the pleasures of watching her “daughter” evolve from a teenager to an adult, while her other “children” afford her the joys of interacting with a sprightly eleven-year-old and a delightful preschooler.

Q: So Londa is really a clone? And her sisters are also clones, right?

A: I suppose so, but let me point out that, from the moment it entered the language, the word “clone” has carried misleading connotations. At the instant of its creation, a clone is merely an embryonic genetic echo of whatever adult organism supplied its chromosomes. It’s an identical twin, nothing more. Such a creature will not develop into a zombie, an empathic freak, a doppelgänger, a biddable robot, or any other sort of anomaly. Most so-called cloning stories are really “artificial maturation” or “engineered nurturance” stories, and The Philosopher’s Apprentice is no exception. The first time I discussed my concept for the novel with my editor, Jennifer Brehl, she told me, “Clones are a tedious subject. I want this novel to be about something else.”

Q: So what is The Philosopher’s Apprentice really about?

A: The mystery of morality.

Q: Morality is a mystery?

A: I think it’s one of the most baffling phenomena in the whole universe, right up there with consciousness and the fact of being. Why do human beings act nobly under certain circumstances and abominably under others? More mysteriously, why do we identify certain behaviors as noble or abominable? God doesn’t seem to have much to do with it. Lately the Darwinists have taken an interest in the problem. They won’t solve it, but I wish them luck.

Q: It sounds as if you’re a novelist who benefits from interacting with editors.

A: Well, it certainly helped in this case. Thanks to Jennifer Brehl’s prodding, I came to see that, while Edwina Sabacthani’s crazy experiment in time-lapse motherhood was interesting as far as it went, the core of the novel was the relationship between Mason and Londa.

Q: Is that why you’ve described the book as a cross between Shaw’s Pygmalion and Nabokov’s Lolita?

A: Exactly.

Q: I get the Pygmalion part. Why Lolita? Is Mason a connoisseur of nymphets?

A: Good Lord, no. But, you see, the relationship between the philosopher and the apprentice is highly erotic and, ultimately, romantic — the same arc that Humbert traces in his pursuit of Lolita. And, as with Humbert and Lo, the initial dynamic between Mason and Londa is that of a teacher and his student. I have a teaching degree, and I used to work frequently with school children, mostly helping them make films and videos, so the education theme in The Philosopher’s Apprentice is quite autobiographical.

Q: Your previous novel, The Last Witchfinder — which is quite a good book, by the way …

A: Thank you.

Q: The Last Witchfinder also centers on a teacher-student relationship. The heroine, Jennet Stearne, is tutored by her beloved Aunt Isobel in “natural philosophy,” that is, science.

A: I’d never thought of that connection before.

Q: But whereas The Last Witchfinder is an unequivocal celebration of the Enlightenment, The Philosopher’s Apprentice seems more wary of science and its fruits. In fact, one of the central “characters” in the novel is a weird high-tech womb called the ontogenerator. Initially it functions mainly to bring Londa and her sisters into the world, but then people start putting the machine to some pretty sinister uses.

A: You’re probably thinking of the scenes in which religious zealots pilfer aborted fetuses, turn the biopsied tissue into full-grown adults, and then condition these angry “immaculoids” to torment the parents who presumably canceled their prospective lives.

Q: Those scenes, yes. What the heck is going on here? On one level, the immaculoids are sympathetic, but I don’t think of you as being in the “pro-life” camp. The Last Witchfinder was a very feminist novel.

A: Once I stumbled upon the concept of the immaculoids — these “adult fetuses” with their programmed grudges — I decided to push it to extremes. Who knows, maybe I imagined that this “thought experiment” would help reframe the abortion controversy. What I love about fiction is the way this form of expression allows an author to wrestle an idea to the ground, as opposed to the bumper-sticker dialectics that passes for political and philosophical discourse in most sectors of our culture. In the age of mass communication, we need the quiet, contemplative, and often ambiguous medium of the novel more than ever.

Q: You’re avoiding the question, Morrow. By bringing those wretched immaculoids on stage, don’t you end up endorsing the anti-abortion position?

A: While composing The Philosopher’s Apprentice, I did some public readings of the immaculoid scenes that, halfway through, had some audience members wondering if I might be taking a “pro-life” stance. By the end of the immaculoid episode, though, it’s pretty clear that I’m satirizing those ideologues who fetishize fetuses but don’t seem to care very much about people. The immaculoids mean nothing to their creators apart from their utility value as an anti-abortion icon.

Q: You obviously have a taste for grandiose themes. Where does that come from?

A: No cleric will tell you this, and most philosophers, scientists, educators, and politicians also want to keep the cat in the bag, but it would appear that human beings haven’t the foggiest idea why there’s intelligent life in our part of the galaxy, nor do we have a glove on why any one of us has been hurtled onto this planet, at this moment in cosmic time, in whatever immediate circumstances he or she happens to enjoy. But I figure that, given our “thrownness”, as Heidegger called it, we should work hard to become as bewildered as possible by this strange state of affairs, asking the most impertinent and audacious questions we can imagine. To do otherwise — and instead hand over the mystery of it all to dubious cults of expertise — is to waste one’s life, I feel.

Q: So, for you, novels are a good way to keep experts from impoverishing our minds?

A: That’s right. In recent years, in interviews very much like this one, I find myself noting what a privilege it is to work within this particular form. Novels give writers and readers unique ways to grapple with the mystery of it all, and thus continue the great post-Enlightenment conversation.

Q: We’ve talked about Shaw and Nabokov as influences. One of your pre-publication critics, covering the book for Kirkus Reviews, notes that The Philosopher’s Apprentice also “tips its hat with style to Mary Shelley.”

A: Frankenstein was definitely a touchstone. In fact, for awhile I was calling the novel Prometheus Wept, an allusion to Mary Shelley’s subtitle, The Modern Prometheus. My Londa is indeed a kind of monster: a “moral monster,” that is, cursed with a hypertrophic conscience. And, of course, Frankenstein is one of the great novels about the teacher-student relationship. Victor’s sin is not so much that he abuses his knowledge but that he breaks faith with his creation. He fails in his primal parental responsibility. To paraphrase Professor Marvel, Victor Frankenstein is a good wizard, but he’s not a very good man.

Q: But eventually Londa becomes monstrous in a more conventional sense, doesn’t she? By the end of the novel she’s almost as brutish as the creature in the Hollywood adaptations of Frankenstein.

A: As part of my calisthenics while writing this novel, I spent a whole week watching virtually every DVD with the word “Frankenstein” in its title, beginning with the Thomas Edison version of 1910.

Q: That must have been quite a marathon.

A: Hour by hour, popcorn bowl by popcorn bowl, I lounged on my couch and watched the alembics boil, the floating brains pulse, the disembodied hearts throb, the peasants light their torches, and the patchwork cadavers shamble forth from the lab. I ended up with a newfound appreciation of the Nietzschean bravado with which Peter Cushing played Victor Frankenstein over the course of six British films for Hammer Studios.

Q: No doubt you could reel off their titles.

A: The Curse of Frankenstein, Revenge of Frankenstein, Evil of Frankenstein, Frankenstein Created Woman, Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed, and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell. While composing The Philosopher’s Apprentice, I also listened to the original soundtracks, which my wife got me for Christmas on audio CD.

Q: It’s always nice to meet a fellow geek.

A: I wanted to suffuse The Philosopher’s Apprentice with a proper measure of celluloid sensationalism. I’ve always liked the truism, “All art is entertainment,” and its variant, “All drama is melodrama.” Sure, it doesn’t work the other way around — but let’s not forget that most serious novelists are out to show the reader a good time. Well, not Henry James, but most serious novelists.

Q: Somebody once remarked, “Henry James chewed more than he bit off.”

A: As opposed to, say, Herman Melville. From page one onward, Moby-Dick is almost polymorphous-perverse in its commitment to the pleasure principle. I wish more English teachers helped their students engage the classics at the level of raw delight, instead of putting them on the scent of symbols. A novel is not a cryptogram.

Q: Nevertheless, when you named your main character Londa Sabacthani, you were obviously trying for a symbolic effect. Her name evokes Jesus’s famous cry from the cross in Matthew 27:46.

A: What famous cry would that be?

Q: “Eli, eli, lama sabacthani.” Translated from the Aramaic, it means, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”

A: No, that was the last thing on my mind.

Q: You’re lying.

A: Yes, I’m lying. Novelists get paid to lie. We must be constantly vigilant, lest it become a habit. Now let me tell you about my dogs.

Q: I’m afraid we’re out of time.

A: We have an amazing female SPCA Border collie named Pooka and a male Doberman mix named Amtrak. He’s a wonderful dog, too. We rescued him from a train station in Orlando, and he’s never forgotten it. Thanks for a very enjoyable conversation.